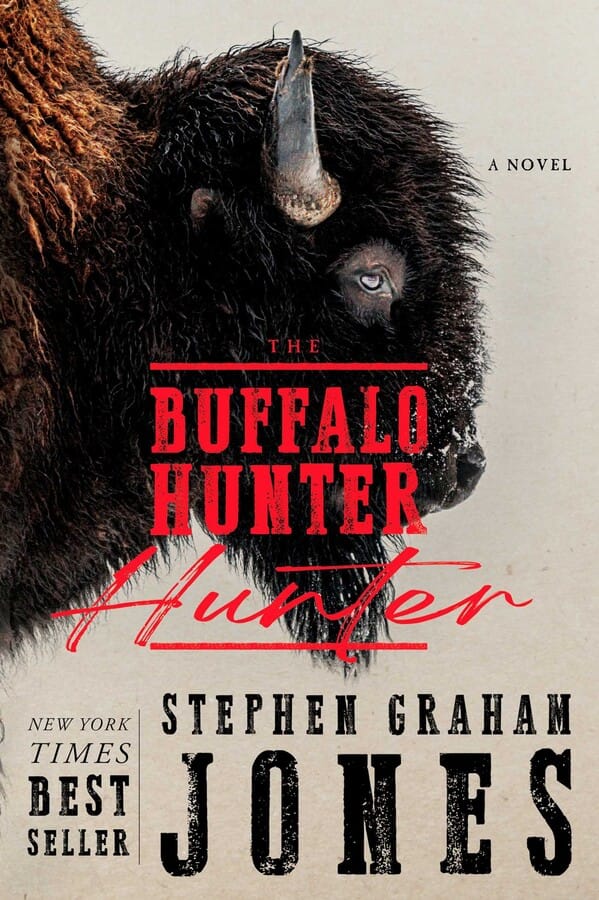

Book of the Month: THE BUFFALO HUNTER HUNTER by Stephen Graham Jones

Ready for the next great vampire novel?

A fun fact about me is that I don't read very many new books. I often joke that my literary taste is fifty to a hundred years out of date. I certainly don't tend to pick up books and start digging into them on the day they come out. But I've made an exception to that habit, because this book has been on my radar for the past several months, and I have eagerly awaited its release. And wow, was it worth the wait.

Stephen Graham Jones is a Native American (Blackfeet, to be more precise) novelist best known for his work in the horror genre. Though his bibliography stretches back to the year 2000, when he published his debut novel The Fast Red Road, he began gaining much more prominence around 2020. The two horror novels he published that year, The Only Good Indians and Night of the Mannequins, both won Bram Stoker Awards and Shirley Jackson Awards, with the former also winning the 2020 Ray Bradbury Prize. Jones would repeat the double Stoker-Jackson feat with his next novel, My Heart is a Chainsaw. Cut to the present day, and Jones has published four more highly acclaimed horror books. His latest publication, The Buffalo Hunter Hunter, came out on March 18th of this year and is already showing up on bestseller lists.

In his work, Jones uses the settings and tropes of horror in order to comment upon indigenous society in the United States and call attention to racial injustices both historical and modern. The Buffalo Hunter Hunter continues that tradition, though the focus is shifted to a slightly different style of horror: while Jones's last few novels had mostly paid homage to slasher films, this one is a reimagining of the vampire mythos in all its undead, blood-drenched glory.

The year is 1912, and Lutheran pastor Arthur Beaucarne lives in the small Montana community of Miles City, ministering to his flock and trying not to dwell on the violent misdeeds of his past. But his tranquil existence is upended when a mysterious Blackfeet man wearing priest's robes and sunglasses begins attending Sunday services. This man is called Good Stab, and he wants to confess his sins to Beaucarne. The pastor may not believe his story at first, he says, but he will see the truth of it in time. Despite his incredulity and bemusement at having a "savage Indian" in his church, Beaucarne agrees to hear the confession. Thus, Good Stab begins a fantastic and horrifying tale that stretches back decades. He claims that in 1870, he was attacked and killed by a monstrous fanged creature—a "cat-man"—and subsequently resurrected as a monster himself, an unkillable entity with heightened senses and a constant thirst for the blood of the living. Cut off from the life he once knew, Good Stab attempts to cling to his humanity and his people's culture in the only way left to him: hunting and killing the white men responsible for the mass slaughter of buffalo herds. Beaucarne first assumes there must be some rational explanation for the story, but as a series of brutal murders begins to consume Miles City—each new corpse skinned like a buffalo—he is forced to confront the awful truth of Good Stab's dark gospel.

With its framing device of a vampire telling his life story to an unsuspecting human, it feels obvious to compare and contrast The Buffalo Hunter Hunter with Anne Rice's Interview with the Vampire. And while the two books may appear to lack similarities beyond that point, I think they share a common goal: rejecting the established tropes surrounding popular vampire narratives and offering up a new vision of what the vampire can symbolize for humanity. Rice was rebelling against the image established by classic horror films of the 30s and 50s, creating vampires that were complex and sympathetic as opposed to merely threatening. Jones, meanwhile, is in part rebelling against the standards set by Rice and her imitators. It's tempting to include The Buffalo Hunter Hunter as part of a recent trend in horror media that seeks to reestablish the vampire as a dangerous and violent monster with virtually no sympathetic qualities (i.e. the last several cinematic depictions of Dracula, including the most recent Nosferatu remake). Jones, however, achieves a remarkable balancing act. He does not shy away from the gruesome and dehumanizing aspects of vampirism, but his vampire is still a complex and tragic protagonist that the reader feels deeply for. He does this by drawing on his unique experiences as a Native American writer, taking a subgenre traditionally dominated by white authors and reframing vampirism as a story of indigenous pain and resistance to genocidal imperialism.

Native Americans are still very underrepresented in stories like this. The most (in)famous example of a vampire novel having a Native character is probably still Twilight, of all things. But in Jones's capable hands, Good Stab is a breath of fresh air and an incredible main character. He hits several of the emotional beats that you'd expect from a vampire protagonist—despairing over his lost humanity, reminiscing about dead loved ones, etc—but his Native identity adds a new perspective to those ideas so commonly expressed in stories like this, and it gives readers a new way to look at the horror inherent in vampirism. This book does something brilliant that you rarely see in vampire novels intended for white Americans: part of the vampire's curse is that he is forcibly separated from his own culture. One of Good Stab's virtues is that he loves the Blackfeet people, their traditions, their beliefs. But as a vampire, he can no longer partake in their way of life: his bloodlust makes him a danger to his own people. He regards his curse as a divine punishment for being tempted away from Blackfeet traditions, for valuing a white man's gun over the life of a beaver. This loss of community is what haunts Good Stab the most throughout his new life. It's the source of his anger and regret, and it's the force that drives him to protect his people from afar by killing the buffalo hunters. Reading the sections that he narrates, you're horrified by the acts of violence he commits, but you feel deeply for him all the same.

Jones devotes the same amount of care and attention to creating the character of Arthur Beaucarne, the unwitting mortal who stumbles across dark secrets man was not meant to know. As someone who has read a lot of fiction (especially horror fiction) from the late nineteenth/early twentieth century, I'm extremely impressed by how well Jones captures the tone of writing from that time period. Beaucarne's journal entries all manage to sound accurate while remaining accessible to modern readers. It's equally hard to write for a character who is supposed to be a talented writer by in-universe standards, but Jones pulls this feat off as well. Through the observations he writes down, Arthur Beaucarne comes off as educated, eloquent and introspective—to a point.

The additional aspect of this sections that Jones's writing really brings to life is the ignorant, paternalistic bigotry often found in white Americans' historical perspectives of Native tribes. It's not the violent, outwardly offensive displays of racism that you might be expecting (though the novel contains depictions of that behavior as well). Instead it's the way that Beaucarne mentally assigns a childlike innocence to Good Stab, an adult man, when they first meet. In his mind, complex reasoning and an understanding of white American culture—English words, Christian beliefs and practices—are beyond the understanding of an uncivilized Indian like his new friend. Not that there's anything wrong with that, he'd be quick to say. It's just the way things are now. He initially assumes that Good Stab's confession will be a quaint tale of yesteryear, the last relic of a people and a way of life that will soon be extinct. But he couldn't be more wrong, and for him, part of the horror is realizing just how wrong he is. Of course it unsettles him to learn that Good Stab is essentially an inhuman serial killer, but learning that this person he thinks is intellectually inferior to him understands way more than he lets on? That Good Stab knows what Beaucarne thinks of him and resents him for it? That's frightening on a whole other level to him. I found it fascinating to read the back-and-forth between these two characters and see how the power dynamic between them changes across multiple encounters.

And of course I'd be remiss if I didn't praise the way this story imagines and constructs vampirism itself. It's clear to me that Jones is very familiar with past cultural depictions of vampires and has put a ton of thought into which tropes he wants to highlight and which ones he wants to avoid. In particular, he does a really great job of eliminating any possible avenues for what we might call "ethical vampirism." It's the having your cake and eating it too of vampire stories: the heroic undead fiend doesn't need to compromise his morals by eating innocent people because he can just eat animals, steal from blood banks, only hunt evildoers, etc. Jones isn't having any of that in his book. One by one, he expertly cuts off every loophole that Good Stab tries to exploit, ultimately exposing vampirism as a gruesome paradox: to retain whatever humanity you have left, you must choose to be a monster.

In The Buffalo Hunter Hunter, the act of drinking blood comes with a lot of consequences that the vampire must accept and strategize around, or else they're going to get screwed over. First of all, feeding inevitably means taking a life. Whenever Good Stab tries to spare one of his victims by only taking some of their blood, it never works: the monster inside him wants to drink as much as it can, and once it's latched on to a living creature, it refuses to let go. And it must be a living creature, because blood from someone who is already dead won't provide the sustenance necessary for a vampire to retain their superhuman senses and reflexes, as well as their ability heal from grievous injuries. Those enhanced abilities are the main benefit a vampire gets from drinking blood; it doesn't directly keep them (un)alive. So in theory, a vampire could perhaps survive without blood...but in practice, the thirst always reasserts its dominance in the end. And when that happens, a vampire doesn't even get the luxury of choosing who they kill.

For me, the most impressive part of the monster-building in this book comes from how Jones closes the loophole of "just survive by feeding on animals." It's a simple but brilliant innovation—these vampires operate on a very literal meaning of "you are what you eat." A vampire who makes a habit of feeding on a single type of animal will gradually start to develop the physical characteristics of that animal. So when Good Stab tries to survive by drinking the blood of deer, for example, it isn't long before he starts growing antlers. In order to maintain a human form, the vampire must choose to hunt and kill humans. I find that to be a more fascinating and thought-provoking idea than if Jones had simply made his vampire unable to consume animal blood. The way that Good Stab deals with this choice and tries to limit its consequences leads to the moral question at the center of the whole book: how far would you go to preserve your sense of identity if it meant betraying your own people?

So once you're out of tricks and loopholes that might allow you to be a "good" vampire, what are you left with? Nothing but the urge to consume. That's what vampirism is all about in this story: taking from the world around you until there is nothing left to take, for no greater goal than satisfying your own hunger. Nothing about it is beautiful or romantic, nor does it fulfill any kind of power fantasy. It's an ugly, brutal, dehumanizing existence that destroys the vampire as well as their victims. And the book makes a strong political statement by drawing a parallel between its fictional horrors and the real-life exploitation and genocide carried out against Native tribes by the United States. Killing and displacing whole nations of people, depriving them of the resources they need to survive, taking their land to sustain yourself and grow more powerful—what is that if not a more abstract, large-scale and much scarier form of vampirism? Good Stab is a ruthless killer in his worst moments, certainly. But coming across an entire field of slaughtered buffalo, their skinned corpses left out to rot so the Blackfeet cannot use them, is a level of horror that neither he nor any other imaginary monster could aspire to.

The Buffalo Hunter Hunter is an incredible book and just the thing to read if you're in the mood for some dark, complicated and thought-provoking horror. Stephen Graham Jones offers up a bleak and uncompromising vision of the vampire as a tragic monster, blending familiar folklore with creative new ideas, diverse perspectives and sharp political commentary. The richness of the novel's dialogue and narration immerse the reader in its Old West setting, illuminating some dark pieces of American history with stunning prose. The main characters are complex and compelling, springing off the page through their words and deeds. I would highly recommend listening to the audio version of this book if you have the chance, since the narrators' performances enhance the great dialogue even more. But no matter which format you choose, you should pick up this book as soon as possible if you're a horror fan. Want some vicious kill scenes and imagery soaked in gore? You'll find it here. How about melancholy introspection on the tragedy of losing your cultural identity? You'll find that here, too. Deep and disturbing, this is the kind of book that will sink its teeth into you and leave a permanent mark.

This was my Book of the Month pick for March. Check back later this month for my April pick!

—Dana