Today on Project Gutenberg: "Bluebeard"

It's a classic fairy tale, but can it become something even better?

Today on Project Gutenberg, we have...

The Popular Story of Blue Beard by Charles Perrault

Of the numerous European fairy tales collected by the likes of France's Charles Perrault and Germany's Brothers Grimm, the story of Bluebeard is an odd one. It's almost completely devoid of the magical phenomena that feature so prominently in other fairy tales. You'll never see a Disney movie based on it because it can't be cut down into a sanitized, family-friendly product. Its narrative is threadbare, and its ultimate point is little more than "Look at all that, wasn't that fucked up?"

And yet, the story's popularity has endured right up to the present day. It's been reinterpreted and adapted through the mediums of film, literature, opera, comic books and even tabletop roleplaying games. Storytellers keep revisiting the tale of Bluebeard because, I think, it's perfect for being told in new ways that build on the existing dark subject matter and introduce new adult themes to the narrative. In fact, I think the story is best examined not as a fairy tale, but as a work of proto-Gothic literature.

The earliest written version of Bluebeard, attributed to Perrault, was published in France in 1697. If put into a timeline of Gothic fiction, it would predate Horace Walpole's The Castle of Otranto (considered the official origin of the genre) by sixty-seven years. The version I have found on Project Gutenberg is an English translation published in 1828. The translator of this version is not named, and they appear to have embellished/extended the original text somewhat. But the essence of the story remains, and it goes like this:

Bluebeard (so named on account of his unfortunate facial hair) is a filthy rich but ugly nobleman who wants to get married. Buried a few paragraphs in is the detail that he's been married before, but no one knows what happened to his previous wives. Bluebeard sets his sights on a pair of beautiful young sisters, Fatima and Anne. If you're wondering why one sister has a Middle-Eastern name and the other is just Anne, we'll get to that. Both sisters initially object to the idea of marrying Bluebeard, but after he invites them to his estate and shows off all his wealth, Fatima decides that he's not so bad. She gets married to Bluebeard, and both sisters go off to live in his castle. Sound normal so far? Too bad, it's about to get weird.

Shortly after the wedding, Bluebeard must leave on a trip for vague reasons. He gives his wife the keys to all the doors in the castle and says she is free to open any of them except for a certain small, nondescript closet. "If you do not obey me in this," he says, "expect the most dreadful of punishments."

To her credit, Fatima listens at first. But after having done everything you would do if you had a castle all to yourself—throwing a giant rager of a party where you invite all your friends and your previously unmentioned brothers—her curiosity finally gets the better of her, and she ventures into the mysterious closet.

Surprise, surprise, said closet contains the bloody mutilated corpses of Bluebeard's previous wives, executed for their disobedience. Fun! And Fatima soon realizes she'll be next on the chopping block, because there's indisputable evidence that she went into the forbidden room: some of the blood from the corpses has magically bound itself to the closet key, staining it. This, by the way, is the one supernatural plot point that allows us to classify this as a fairy tale.

Bluebeard comes home the next day, finds the bloody key and essentially tells Fatima "Welp, tough luck but I'm gonna kill you now, that's what you get for being nosy." Fatima, however, is able to stall for time by asking Bluebeard to let her finish her prayers before he kills her. This is what ends up saving her life, because right as she's about to get decapitated, her brothers show up as a deus ex machina to kill Bluebeard for her. Fatima inherits all of Bluebeard's wealth, which she gives away to her family and friends, and gives the murdered women proper burials. Eventually she remarries to a guy who's not a serial killer, and the traumatic encounter with Bluebeard is forgotten. The End!

So, this story kinda sucks. I don't mean the Bluebeard narrative itself, I mean this particular telling of the story that we've found on Gutenberg. The run-on sentences and overly flowery language are a departure from the original French text, and all they really do is make the prose more awkward and bloated than it needs to be. If you compare this text to a more accurate translation, like the one in Andrew Lang's Blue Fairy Book, you'll find the latter to be less detailed but much easier to read.

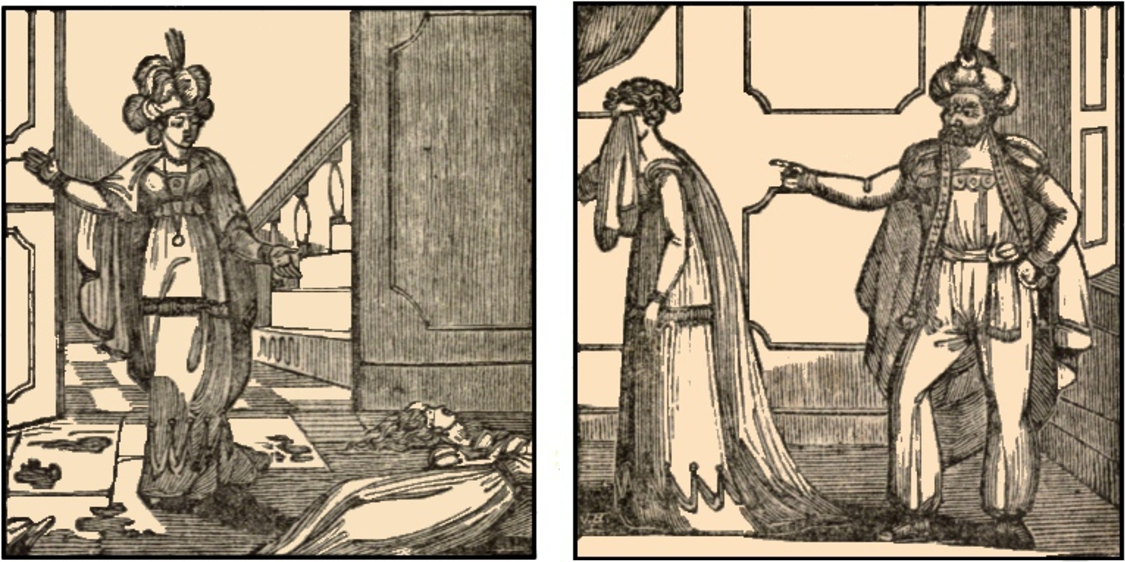

The other big problem with this version is one that, as it turns out, many 19th-century retellings of Bluebeard share: weird Orientalism. The story comes from France, and the sources/people which may have inspired it all come from French history and folklore. But that didn't stop artists and writers from relocating the narrative to the Middle East or just depicting Bluebeard himself with stereotypical Arab features and dress. The translation we've been looking at is somewhat guilty on both accounts: it deliberately avoids naming a setting and gives the wife a Middle Eastern name, but every character except Bluebeard is depicted as European in the accompanying illustrations. Bluebeard himself is drawn with Middle Eastern robes, a turban, he tries to kill his wife with a scimitar, etc. You get the idea. Multiple theories exist as to why this is, but the idea underpinning most of them is the same: the violence of the story was, to readers of the time, not something that a European nobleman could or should be depicted doing. Better to give the audience a more exotic villain and avoid those uncomfortable implications you'd have otherwise.

This is why the best Bluebeard retellings, in my opinion, come to us from the 20th and 21st centuries. They don't seek to push away the darkness of the narrative—instead, they embrace it.

I want to return to the idea of Bluebeard as a proto-Gothic text. I call it that because it's not a true example of Gothic fiction in its original form, and yet its premise—an innocent young woman weds a tempestuous older man with secrets about his past involving previous relationships—is practically the stock plotline in Gothic fiction. Jane Eyre is the classic example, albeit with a living wife locked up in the husband's forbidden room. Daphne du Maurier's Rebecca amps up the mysterious, foreboding elements of the heroine's situation and reintroduces the murder twist. Guillermo Del Toro's 2015 film Crimson Peak, a love letter to all kinds of Gothic tropes, replicates the Bluebeard narrative almost perfectly in its main plot.

By now you should be asking "If Bluebeard has such an influence on this subgenre, why don't we consider it part of that subgenre?" The answer is really pretty simple: the tone's all wrong. Dark and harrowing things happen in the story, but it's all described with the detached narration that most traditional fairy tales have, lessening the actual horror. Bluebeard's castle lacks any Gothic imagery outside of the one murder closet. Instead, it's consistently described as this dazzling and well-kept palace that lacks any sinister qualities whatsoever. The protagonist is not physically or emotionally isolated, nor is she psychologically challenged all that much. Not only does she have a network of family and friends to rely on (a rarity for Gothic heroines), she doesn't actually have any problems until the exact moment she opens that closet door. And once Bluebeard is killed, she moves on pretty quickly without any lasting trauma.

In short, Bluebeard in its most basic form can be described as a non-Gothic story that's primed to be made Gothic through reinterpretations. And that's why the best version of this story by far is Angela Carter's The Bloody Chamber, which you should 100% read instead of this weird 1820s version. Hell, you can read that story instead of Perrault if you really want to. Perrault will give you the essential pieces of the story, but if you want to see how its full potential can be realized—how it can be used to make statements about society, feminism, violence and abuse, sexuality and relationship dynamics—then you should see what modern storytellers have done with it in decades past and continue to do with it today.

And that's what we found today on Project Gutenberg. Thank you for reading, and I'll see you next time!

—Dana