Today on Project Gutenberg: "Through by Daylight"

All aboard for Melodrama Station!

Today on Project Gutenberg, we have...

Through by Daylight by Oliver Optic

There are two things (among others) that I've already dealt with enough in my life. One is steam trains, and the other is 19th-century boys' adventure novels. Thus, I naturally hesitated when Project Gutenberg's random search function offered me up a 19th-century boys' adventure novel with a steam train in it. But I am glad I didn't pass this one up: while I wouldn't call it a lost gem, it's more entertaining than I expected it to be.

The official title of today's book is Through by Daylight; Or, the Young Engineer of the Lake Shore Railroad. Its author is listed as Oliver Optic, a name too good to be true—because it is. "Oliver Optic" was the pseudonym of William Taylor Adams, an author from Massachusetts. Having spent many years as a schoolteacher, Adams had a good idea of what literature most appealed to children, particularly boys. He wrote over 100 books between 1853 and his death in 1897. The majority of these books were grouped into series, mostly intended for boys but a few intended for girls as well.

Through by Daylight, published in 1869, belongs to the former category. It was the first book in what Adams called the Lake Shore series. He claimed that the plot was loosely inspired by a real railroad in Ohio, called the Miami Valley Railroad. It's unclear if he's telling the truth here, though, since no railroad of that name operated in Ohio prior to 1876. More importantly, Adams describes his protagonist as "an example of the moral and Christian hero, who cannot lead his imitators astray; for he loves truth and goodness, and is willing to forgive and serve his enemies." This, as we shall see, turns out to be only mostly true.

Our protagonist is a stubborn little shit (and I use that term affectionately) named Wolfert "Wolf" Penniman. Wolf loves steam engines, knows all about them and hopes to follow in the footsteps of his father, who is an engineer. When the money for the family's mortgage is stolen, Wolf takes it upon himself to find work and keep his parents out of poverty. Doing so, however, requires him to decide if his loyalties lie with his hometown of Centreport or the rival town of Middleport, which is currently building its own railroad. All sorts of action and drama ensue until we arrive at the prerequisite happy ending.

The basic plot points of the book are nothing special. Overall, this is another one of the Horatio Alger-esque "poor boy makes good" narratives that appeared in most American children's literature of this time period. The part of it that got my attention was the characters and the actual writing.

Compared to the protagonists in other examples of this subgenre that I've read, Wolf acts a little bit more like an actual teenager as opposed to a paragon of virtue. Don't get me wrong, he's meant to serve as a role model: he's unfailingly honest, he's there to help when people need him, and he's opposed to alcohol consumption of any kind. But he's also snarky and opinionated. He resents the idea that he's supposed to genuflect to those of a higher social class than him, and he recognizes that even the "good" wealthy characters are arrogant, impulsive and expect a certain level of deference that they haven't necessarily earned. Although he generally respects authority, he has no use for an authority that doesn't respect him back. For example, this is how he talks about the villains of the story, a rich spoiled brat named Waddie and his father Colonel Wimpleton, the de facto mayor of Centreport:

- "I am not a rascal, Colonel Wimpleton. If either of us is a rascal, you are the one, not I," I continued, goaded to desperation by his injustice.

Now, does Wolf talk like a teenager probably would have in the 1860s? I doubt it. But his narration does give the story a bit of character that is sorely lacking in other books of this sort. To put it bluntly, I think this book would be a lot less tolerable if it was not written in first-person POV. Writing in the mind and voice of this character who would otherwise come off as a more two-dimensional protagonist is a slight but still noticeable improvement.

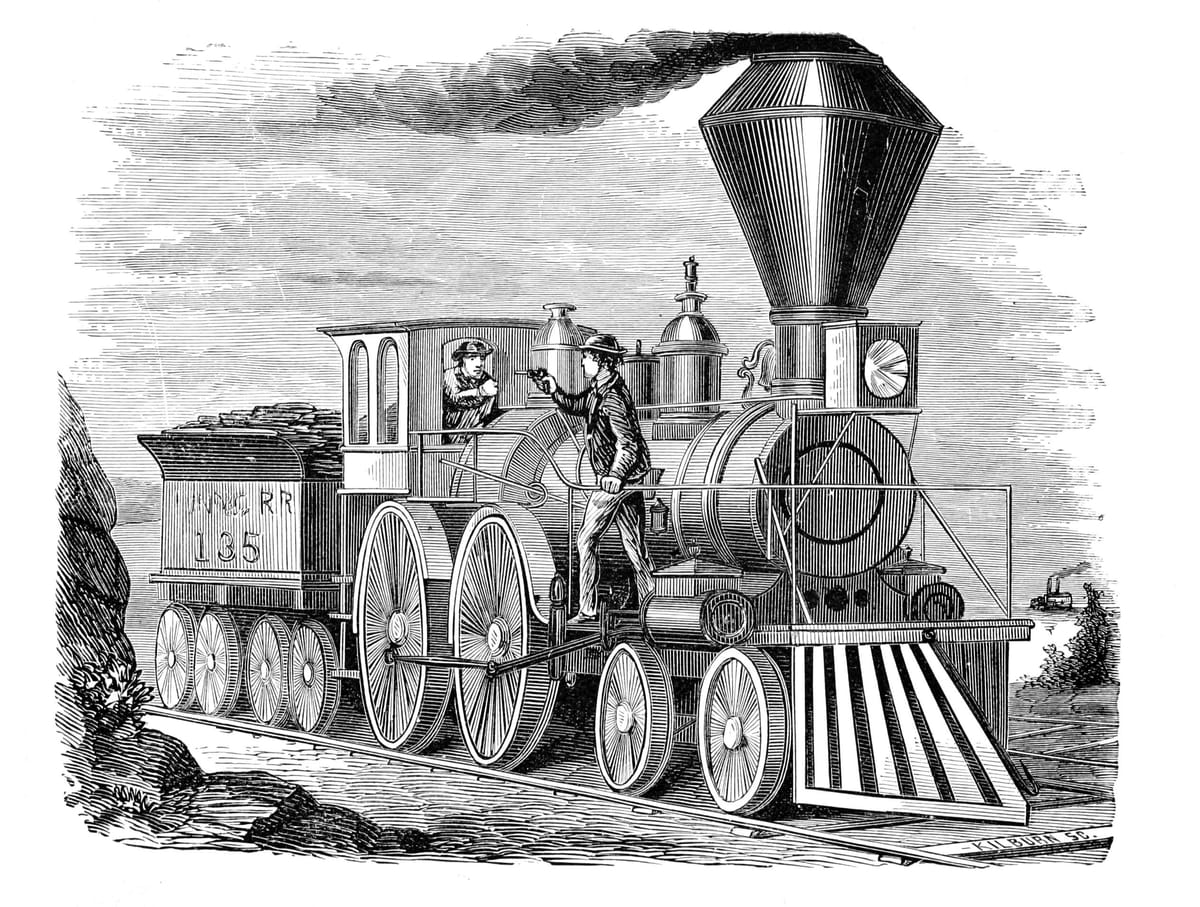

Hearing Wolf's story in his own voice makes the narrative a little less annoying and a little more charming. Which is good, because a lot of ridiculous stuff happens in this book, both of the wish fulfillment variety and of the "pure chaos" variety. This is a story in which the teenaged villain attempts to commit murder several times, starting with what is arguably an act of terrorism in Chapter 2 that he tries to frame the hero for. There are runaway trains, trains getting derailed, trains falling in a lake and dramatically being pulled back up. Betrayals! Sabotage! Children pulling guns on adults! And most of it is done without the offensive racial stereotypes so often present in books like this (outside of a few paragraphs at the very end of the story).

In conclusion, Through by Daylight may offer some amusement to a reader with a fascination for 19th-century boys' literature. While the content of the story is not especially remarkable, the author's choice to use first-person POV gives the protagonist a little more personality than some of his literary contemporaries. You could do much better than this, but you could also do much, much worse.

And that's what we found today on Project Gutenberg. See you next time!

—Dana